Arcade Console

Arcade Console is a project commissioned by Carleton College in November of 2003 for the exhibition State of the Art: Maps, Stories, Games and Algorithms from Minnesota, curated by Steve Dietz. The piece is a custom-built arcade cabinet created to mimic the look, feel and experience of a real arcade machine and includes virtually every arcade game ever created. It is at its core an archival project, one that allows the user to look back at a history of gaming they may never have otherwise been allowed to, with an experience that is true to arcade gaming's roots.

The project started as a personal one. I had originally decided to build a custom built arcade that ran MAME in my spare time. Several proof of concepts followed of control panels hooked up to various computers. I had estimated the process would take about 3 years of development as I slowly worked on the project. Steve knew about the control panel prototypes, and when he got the go ahead to curate the show at Carleton College, he asked if I could finish the project for the show. This accelerated the timeline from 3 years to 3 months. Work was ramped up and the project was completed two weeks before the show opened.

Photos of the entire project can be found on Flickr.

Prototypes

The first prototype was basically just a joystick and buttons in a cardboard casing. The initial design was to see how hard it would be to hook up to a computer and play a game. As time permitted I added another controller and finally a trackball and spinner to the prototype. The third and final prototype in July of 2003:

Planning

After conrol panel prototypes were created, planning began on the actual cabinets as well as the electronics. The cabinet itself was modeled after a Super Monkey Ball cabinet. There happened to be one at the local Gameworks that I went to and measured the dimensions of.

From this I was able to create several CAD drawings of the dimensions. This gave a piece by piece view of what was to be made for the cabinet. I also made a more detailed CAD drawing of the control panel, which was the most complicated piece to build.

From these diagrams we could put together a cabinet shell to house the electronics, etc. A lot of research was also spent on how to do most of the electronics, although a lot of this was already set after doing the control panel prototypes.

Parts

After the CAD drawings and all planning was set, it was time to buy all of the parts needed to build. The parts list includes:

- Cabinet

- Birtch Plywood (3/4" wide)

- Wood Screws

- 4 Casters

- 2 Piano Hinges

- 2 Friction Clips

- 12" Chain

- Locking Mechanism

- Black Formica

- Black Gloss Paint

- Computer

- ASUS Socket A Motherboard

- AMD Athlon XP 2100+ CPU

- MasterCooler CPU Fan

- Antec 380W Power Supply

- Western Digital 80 GB Hard Drive

- Corsair 512 MB DDR RAM

- Arcade VGA Video Card

- Apple CD-ROM Drive

- Netgear 801.11g Wireless PCI Card

- Controls

- 2 Sanwa 4/8 Way Joysticks

- 14 Happ Pushbuttons

- Oscar Discs of Tron Replica Spinner

- Golden Tee Trackball

- Misc Parts

- Wells Gardner D9200 Arcade Monitor

- I-PAC Keyboard Encoder

- OptiPAC Optical Encoder

- Black Monitor Bezzel

- Coin Mech (dual 25 cent slots, with collection)

- Computer Speaker Amp (hacked)

- Arcade Speakers

- Speaker Grills

- Wire (lots)

- Lucite

- Flourescent Light

- Power Strip

- MAME Marquee

- Marquee Retainer

- Velcro

Building

Building started in two phases. One was the cabinet building, built by my father (a carpenter of 40 years) based on my CAD drawings. The rest of the cabinet, all electronics and putting it together was finished by myself.

The first task was to get the computer up and running with the new monitor, video card, etc, to make sure it all worked properly. It's easier to do it this way than to do it when it's all hooked up inside the cabinet.

Next was actually building the cabinet. We used plywood for the cabinet instead of MDF which is normally used. This for several reasons. Plywood is much lighter, more pliable, and more resistant to moisture. It is also more expensive and harder to work with. It's a trade off I was willing to take for a longer lasting product. One unique aspect of the cabinet is there is no T-molding. All molding is actually wood, creating a nice rounded edge around the entire cabinet.

Perhaps the hardest part was the control panel. Everything had to be exact to fit all of the controls in properly. It took an entire afternoon of measuring, routing, drilling, etc, to get the board the way I wanted it.

In the finished control panel, notice everything is flush mounted. There are no visible screws or bolts. This is on purpose. You will not see screws or bolts anywhere on the exterior of the cabinet.

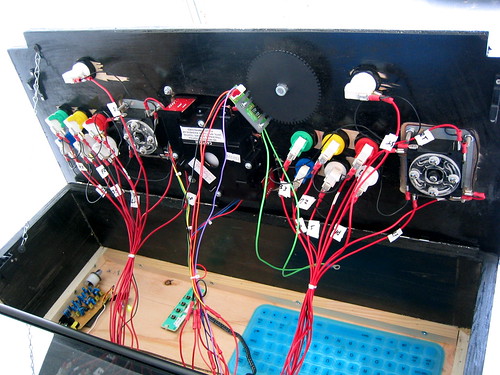

After the cabinet was complete, all that was left was putting in the parts and wiring the cabinet. Given my time spent doing prototypes, this was straight forward, however rewiring everything takes a bit of time. There are quite a few wires, boards, and components to connect.

Finally the cabinet was done and ready to play.

Software

Arcade Console runs Windows 2000. The frontend used for selecting games is MameWah. MameWah's default skin isn't very pretty so I designed my own custom skin for the arcade.

To select a game, you can use the joysticks or trackball to scroll through the list. Pressing the start button loads the game. Games are run with MAME and all controls are mapped correctly to each game. Every game is output at its native res on the arcade monitor. There is no scaling, filtering, etc. The goal is to get as authentic an experience as possible.

Exhibition

Arcade Console was commissioned by Carleton College in November of 2003 for the exhibition State of the Art: Maps, Stories, Games and Algorithms from Minnesota, curated by Steve Dietz. It was very popular with patrons visiting the galleries. In fact, many high scores still exist on it from people who played it during the show.

The following is the curators statement on the project:

Arcade Console is a veritable history of the arcade video game, from Gun Fight (1975) to Metal Slug 3 (2000). Over 4,000 games in all. At its heart is MAME, the Multiple Arcade Machine Emulator, an open source project initiated by Nicola Salmoria in 1997, which is designed to document the hardware (and software) of arcade games - and which also allows them to be played.

An emulator is a software program that runs on a very fast pc (in the case of Arcade Console a 1.7Ghz AMD Athlon) which can emulate other hardware and software platforms. Combine this with the original arcade ROMs, the "read only memory" that contain the actual software instruction set for a particular game, and it plays as if it is on the original hardware platform, so that literally thousands of different games can be played through the Arcade Console interface, which Gustafson has constructed with the help of his carpenter father and programmed to work seamlessly.

Video gaming is often thought of as a subculture, and Gustafson's attention to authenticity has the fervor of any true believer. The spinner is from the classic Discs of Tron game; the trackball is from Golden Tee Fore; the joysticks are from Sanwa Japan, the monitor is a special 27" Wells Gardner arcade monitor. But in fact, measured by usage, the gaming industry is mainstream. It is larger than the movie industry and more people play video games than read books by far. Video games are a major part of contemporary culture, and a project like Arcade Console taps into the efforts of hundreds of people to preserve this important but vanishing "arcade chapter" of gaming history - an effort which it would behoove many so-called mainstream institutions to emulate, if they are to fulfill their mission as chroniclers of the contemporary.

-Steve Dietz

Exhibition History

State of the Art: Maps, Stories, Games and Algorithms from Minnesota

Carleton College Art Gallery

Northfield, Minnesota

Nov 2003